Why do so few women hold high office in the ruling Chinese Communist Party?

Share

Waitresses serve tea to delegates before the opening ceremony of the 20th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party in the Great Hall of the People in Beijing, Oct. 16, 2022.

Not long after the beginning of China’s 1966-69 Cultural Revolution, late Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Chairman Mao Zedong is famously said to have highlighted the contributions of women to the nation by pointing out that “women hold up half the sky.” So why is it that, nearly six decades later, we see so few women actively involved in China’s party congress?

This year’s event kicked off on Oct. 16 with yet another leadership rostrum filled with row upon row of dark-suited men, served by young, slender red-clad women pouring tea and water.

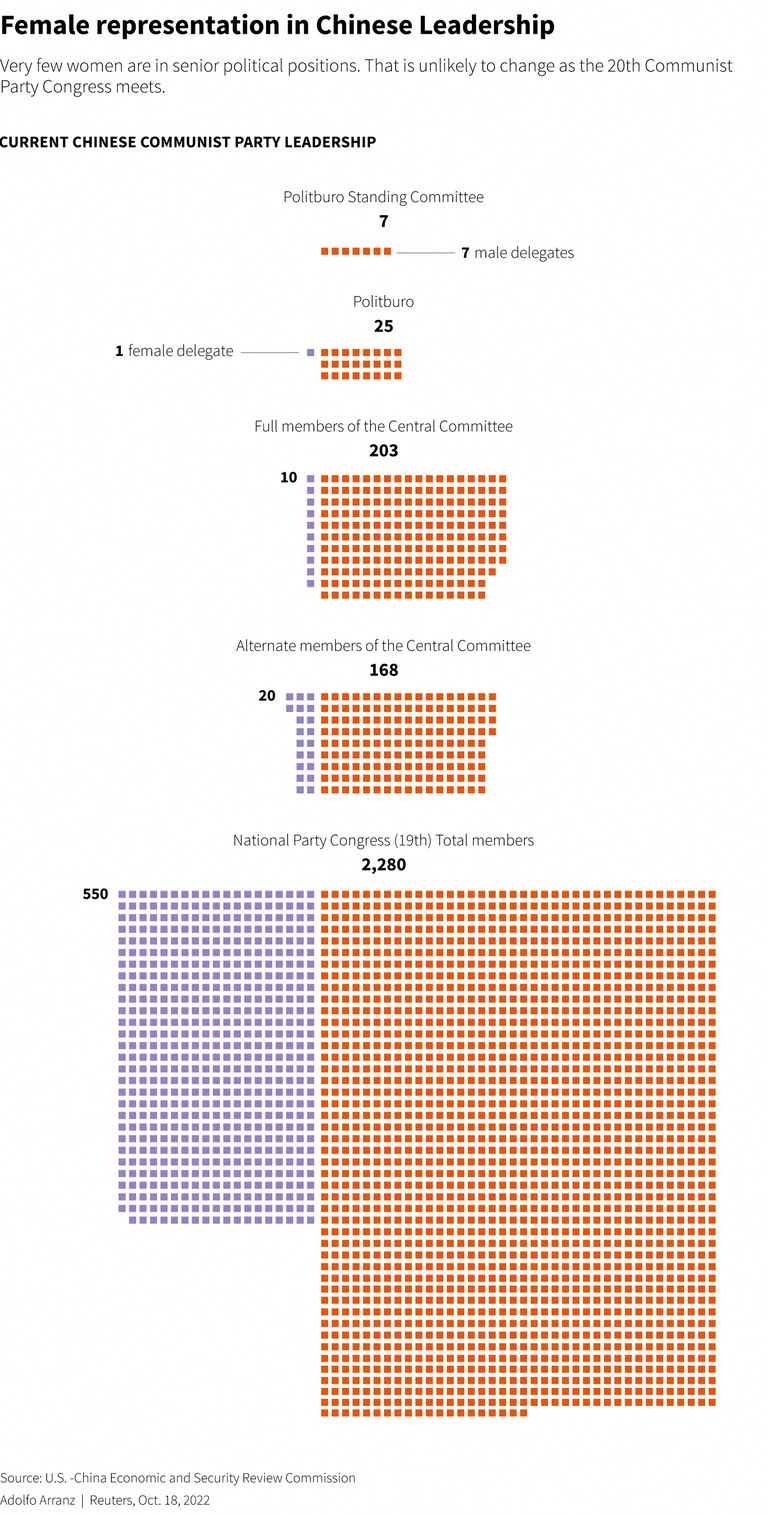

Meanwhile, the CCP’s 25-member Politburo currently only includes a single woman, with vice premier Sun Chunlan, 72, likely to take retirement after the current 20th National Congress.

Just three women, trade minister Wu Yi, former United Front Work Department chief Liu Yandong and “Iron Lady” Sun have served on the Politburo since the 1990s.

Even during the early days of the People’s Republic of China under Mao, high-ranking women like Deng Yingchao, Ye Qun and Jiang Qing never made it onto the all-powerful Politburo standing committee, and gained the clout they did via powerful husbands.

Feminists say the lack of representation at the very top is hardly surprising, given that gender discrimination is still rampant in the workplace at all levels of employment, political or not, in China.

“There are severe restrictions on women’s participation in politics,” Wang Ruiqin, a former member of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference from Qinghai province now living in the United States, told RFA.

“It’s very common for female comrades to be restricted by a glass ceiling because they are women,” Wang said. “This occurs everywhere.”

“They never say you didn’t get the job because you’re a woman; they’ll use any other excuse they can think of instead,” she said.

“But it’s pretty clear that it’s because of limitations on women.”

And it’s not just women in politics. In the wider world, Chinese women still face major barriers to finding work in the graduate labor market and avoid getting pregnant if they do land a job, out of concern their employer will fire them, a common practice despite protection on paper offered by China’s Labor Law.

Likely women candidates

Likely women candidates

According to an unwritten convention, at least one seat in the Politburo must be given to a woman.

After Sun Chunlan retires, any woman entering the Politburo will need to be promoted from the middle ranks of the party.

Likely candidates include Chen Yiqin, secretary of the Guizhou provincial party committee, and Shen Yueyue, vice chair of the National People’s Congress (NPC) standing committee and head of the CCP-backed All-China Women’s Federation.

Lower down the ranks, the numbers are slightly better.

Currently, there are 619 women delegates at the current party congress out of 2,296 — 27% in all, and an increase of 2.8% compared with the 19th party congress five years ago.

According to figures from the International Parliamentary Union (IPU), 31.2% of European parliamentary seats are held by women, on average, with the proportion falling to 21% in Asian parliaments and 16.8% in the Middle East.

However, women hold just 8% of seats in the CCP’s 371-member Central Committee, while only two women hold provincial leadership rank out of a total of 31 posts.

While the proportion of female CCP members rose from 24% in 2012 to 29% in 2021, gender parity is still a long way off.

Women’s rights worse under Xi

Despite lip service to women’s rights from high-ranking officials, and supposed protections for gender equality in the Chinese constitution, women’s rights have worsened during CCP leader Xi Jinping’s decade in power.

A slew of high-ranking sexual assault and harassment allegations under the Chinese #MeToo campaign, the detention and prolonged incarceration of five feminist activists on International Women’s Day and high-profile incidents of violence against women, including the Tangshan restaurant attacks and the Jiangsu “chained woman” scandal, have brought the issue to the forefront of public opinion.

An ongoing crackdown on non-government groups and feminist activists including journalist and #MeToo researcher Sophia Huang has sent out a clear message that the CCP under Xi will brook no challenge to the absolute authority of a patriarchal state, however.

“China has always been a patriarchal society, and there has been no change,” U.S.-based feminist writer Xiang Li told RFA. “The current leadership of China is very clearly suppressing the feminist movement.”

She said a lack of women in policy-making roles only exacerbates the problem.

“Women have first-hand experience of their own needs and of the degree to which they are oppressed by society,” Xiang said.

“Without more preferential treatment of women in the formulation of policy, I’m certain that Chinese women will face increasing difficulties when it comes to protecting their rights and interests,” she said.

National ‘baby machines’

Instead, women’s bodies are viewed by the CCP as the instruments of state power and the “national interest.”

Data from China’s 2020 census showed that the country is currently facing a population decline and falling fertility rates, prompting the government to shift to a “three-child” policy in 2021, after abolishing the decades-long “one child” family planning policy in 2016.

Yet women have responded in interviews with RFA and on social media by saying they lack the time, money or energy for more children, with others slamming the government policy for treating them like “baby machines.”

Meanwhile, hundreds, possibly thousands, of Chinese women are still seeking redress after their health was destroyed by botched or untested reproductive procedures aimed at keeping births within targets set by Beijing, victims told RFA in April.

Xiang said that both limiting births and encouraging them is a violation of women’s reproductive rights.

China currently ranks 102nd out of 146 countries in the World Economic Forum’s gender gap ranking, down from 69 in 2012, when Xi Jinping came to power at the 18th party congress.

Translated and edited by Luisetta Mudie.