US debt deal nears, but Asia will look on warily

Share

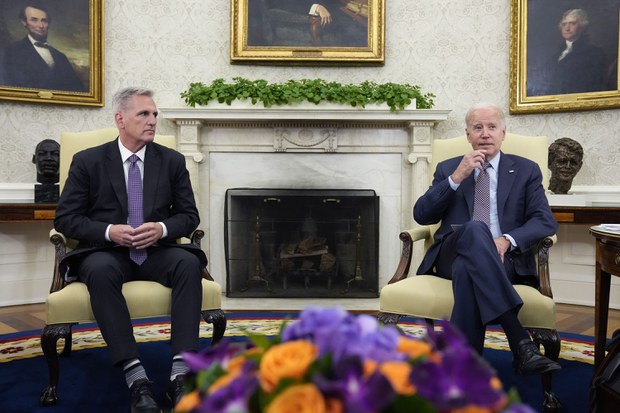

President Joe Biden meets with House Speaker Kevin McCarthy of Calif., to discuss the debt limit in the Oval Office of the White House, May 22, 2023, in Washington.

After weeks of brinkmanship, American lawmakers may finally be approaching a deal that would raise the U.S. government’s “debt ceiling,” allowing it to pay its debts – held in the trillions of dollars by world governments and pension funds alike – on time.

Such a last-minute deal would ensure Washington’s divisive politics once again avoids torching the global economy by blowing up what is widely considered the world’s safest long-term asset: the debt issued by the U.S. Treasury, backed by the immense American tax base.

That would prevent the worst possible spillover of wrangling between Democrats and Republicans across global borders. But much damage to America’s reputation, experts say, will have already been done.

U.S. foes, in particular, would be pleased with the reminder of the indivision that can paralyze Washington, said Ryan Hass, the Michael H. Armacost Chair in Foreign Policy at the Brookings Institution.

“The debt ceiling standoff is an early Christmas present for China and Russia,” Hass told Radio Free Asia. “They both seek to portray the United States as being hobbled by internal divisions and generating dysfunction that does harm to the rest of the world.”

Cascading financial ruin

Such a depiction could have a devastating impact on America’s reputation across Asia, given the deep economic consequences it could cause if those holding the “safe” asset end up shortchanged.

Japan, according to Treasury data, is the world’s largest holder of U.S debt, with more than US$1.1 trillion, followed closely by China itself, which claims some $860 billion. Taiwan holds the tenth-most, at $235 billion, while India holds $232 billion and Singapore $187 billion.

In 17th place, South Korea, meanwhile, holds about $106 billion.

Any failure on behalf of the U.S. government to pay some of its debts to those countries would cause cascading financial damage, as key economic actors themselves wind up unable to pay debts on time.

But even if the debt limit is increased, the now nearly annual exercise of uncertainty and brinkmanship will chip away at the perceived reliability of long-term U.S. debt repayment and likely cause financial planners around the world to further diversify their holdings.

Credit-rating agency Fitch this week put U.S. debt’s coveted Triple-A rating, which lets the United States borrow money at the lowest price, on “negative watch,” citing the “increased political partisanship” in Washington it said was constantly putting repayment at risk.

The agency noted Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen has estimated the U.S. government would run out of money to pay its debts on Thursday, June 1, if Congress does not raise the debt ceiling and approve Treasury’s ability to issue more debt to pay those now coming due.

“The brinkmanship over the debt ceiling, failure of the U.S. authorities to meaningfully tackle medium-term fiscal challenges that will lead to rising budget deficits and a growing debt burden signal downside risks to U.S. creditworthiness,” Fitch said in a Wednesday report.

“The failure to reach a deal to raise or suspend the debt limit by the x-date would be a negative signal of the broader governance and willingness of the U.S. to honor its obligations in a timely fashion, which would be unlikely to be consistent with a ‘AAA’ rating, in Fitch’s view.”

Chaos is priced-in

Still, not everyone is sure the debt-ceiling fight will cause significant desecration of America’s centrality to the global financial system.

Some pundits, for instance, argue a short-term default would in fact perversely lead to higher world demand for U.S. debt, because in the absence of any alternative asset in a time of global chaos, it would still be viewed – in relative terms, at least – as the world’s safest asset.

Others have noted that China – the only economy big enough to offer an alternative to U.S. debt as an asset – would, as its second-largest holder, be as financially devastated as anyone by a default

But even then, Washington’s allies would understand by now that things will never get that far, with the intense last-minute politicking widely viewed as par-for-course for American democracy, said Denny Roy, a senior fellow at the East-West Center in Honolulu.

“Generally, U.S. friends and allies in the region understand that the U.S. has a vibrant two-party system and that sometimes partisan disputes can result in threats of risky actions,” Roy told RFA. “The danger is other countries, both friends and foes, believing that U.S. politics has become so dysfunctional it might affect U.S. reliability. “

Roy said, though, that the second-order effects could be severe, with the world seeing how domestic politics can hobble U.S. foreign policy.

“Now we see President Biden pulling out of a planned Quad meeting in Sydney,” he said. “If the region sees U.S. internal politics regularly disrupting U.S. foreign policy, this will erode U.S. leadership.”

Pivot from Asia

Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese earlier this month canceled a meeting of the Quad – a loose alliance of Australia, Japan, India and the United States aimed at counterbalancing China – at the Sydney Opera House after Biden said that he would skip it.

Biden instead had to fly back to Washington to engage in discussions with House Speaker Kevin McCarthy, and the leaders of the four Quad nations instead met briefly on the sidelines of the G-7 summit in Hiroshima. Albanese told reporters he understood Biden’s reasons, but days later announced he planned to soon pay a visit to Beijing.

In the end, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, too, made the trip to Sydney anyway, appearing beside Albanese at a packed-out concert venue for a public-relations coup, with Biden’s absence conspicuous.

The Australian prime minister likened his Indian counterpart to U.S. rock sensation Bruce Springsteen, who played at Biden’s January 2021 inauguration and in March received the Medal of Arts from Biden.

“Modi is ‘The Boss,’” Albanese told a packed concert venue.

Systemic risk

The real risk of the debt-ceiling debacle, then, may be what the indivision in Washington tells allies and foes alike about a polarized American political system’s ability to maneuver in times of crisis.

Ja Ian Chong, a professor of international relations and expert in Chinese foreign policy at the National University of Singapore, said that the debt-ceiling fracas had blown-up months of efforts by Republicans and Democrats to depict themselves as unified on Asia foreign policy.

“The debt ceiling dispute calls into question U.S. commitment and resoluteness about maintaining its presence in Asia,” Chong told RFA, noting that U.S. foreign policy on China had become “the only or one of the few areas with bipartisan agreement in the United States.”

At best, Chong said, if such a dispute can “disrupt President Biden’s visit to Papua New Guinea and Australia, this suggests that there isn’t even enough bipartisan support for this [foreign policy] agenda.”

But a worse explanation, he added, is that there is bipartisan support in areas like countering China, but “it is not sufficient to overcome serious domestic partisan differences” due to the quirks of U.S. democracy.

With so much at stake for debt-holders across America and Asia alike, he said, the argument that the near-annual exercise in brinkmanship over the key global asset was just politics was starting to wear thin.

“Of course, there is a claim that this could be politics as usual or electioneering ahead of next year’s presidential election,” Chong said. “Onlookers from Asia are not going to pay attention to these details.”