On UN Human Rights Day, activists, dissidents and defenders Asia lost in 2022

Share

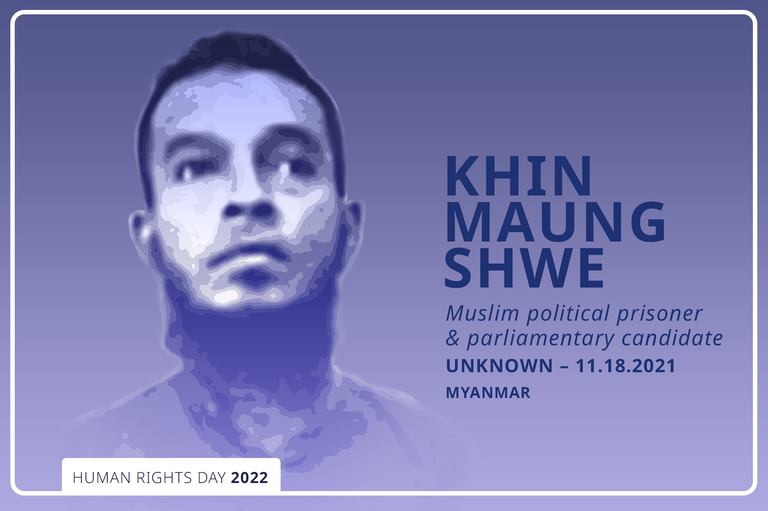

From left: Khin Maung Shwe, Li Jinjin, Bao Tong, Ko Jimmy and Xiong Wei.

In observation of Human Rights Day on Saturday, the 74th anniversary of the United Nations General Assembly’s adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Radio Free Asia is commemorating human rights defenders from the region who died, or whose death was revealed, in 2022.

Under this year’s theme of “Dignity, Freedom, and Justice for All,” the UN is launching a campaign to spread awareness of the key rights document for its 75th anniversary next year.

“For me it’s art that makes my life tolerable. I sang and wrote poetry when my life was rough in prison.” — Ko Jimmy

Veteran Burmese democracy activist Kyaw Min Yu, a writer and translator better known as Ko Jimmy, was hanged at the age of 53 along with a former lawmaker and a pair of activists on July 23.

Ko Jimmy was a prominent leader of the pro-democracy 88 Generation Students Group who fought military rule three decades ago and carried on the struggle against the junta that seized power in a coup on Feb. 1 2021.

He was arrested in October 2021 after spending eight months in hiding and was convicted in a closed-door trial by a military tribunal in January under the Counter-Terrorism Law.

He was accused of contacting the Committee Representing Pyidaungsu Hluttaw, National Unity Government (NUG), and People’s Defense Force (PDF), an opposition coalition and militia network formed by politicians ousted in the Feb. 1 coup that the junta has declared terrorist organizations.

He was also accused of advising local militia groups in Yangon and ordering PDF groups to attack police, military targets, and government offices, and asking the NUG to buy a 3D printer to produce weapons for local militias.

The executions of Ko Jimmy, Phyo Zeya Thaw, Hla Myo Aung and Aung Thura Zaw were decried by UN Special Rapporteur on the Situation of Human Rights in Myanmar, Tom Andrews, as “depraved acts,” while U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken called the executions “reprehensible acts of violence.”

Last week U.N. human rights chief Volker Türk said death sentences have been handed out to 139 people since the military seized power, in trials held “in secretive courts in violation of basic principles of fair trial and contrary to core judicial guarantees of independence and impartiality.”

At least seven student activists were sentenced to death on Nov. 30, with sources telling RFA their execution was set for Dec. 7.

“Anyone who thinks they can export victimhood has already started to take on the quality of a madman. They have left universal values behind.” — Bao Tong

Bao Tong, former top Communist Party aide and key ally to late ousted Chinese premier Zhao Ziyang, died in Beijing on Nov. 9, just four days after he turned 90.

At the time of the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests, Bao served as director of the Office of Political Reform of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party.

Zhao was removed from office after then supreme leader Deng Xiaoping decided his approach to the student-led protests in the spring and early summer of 1989 was too conciliatory.

After his removal from office, Zhao spent the rest of his life under house arrest at his Beijing home, dying in early 2005 with his legacy largely erased from official history.

Bao served a seven-year jail term for “revealing state secrets and counter-revolutionary propagandizing” in the wake of Zhao’s fall from power. But he remained a relentless critic of the Chinese Communist Party, despite spending all of his later years under house arrest or close surveillance at his home in Beijing.

A sharp political essayist, Bao was a long-term contributor of political commentaries to RFA Mandarin, wielding acerbic political commentary and gentle humor by turns, as well as providing fly-on-the-wall accounts of key moments in the history of China.

Bao often blamed the Tiananmen crackdown for human rights abuses, lack of rule of law and other ills that persist in China.

“The massacre paved the way for countless layers of party control, from national government to the urban police, or chengguan, and the auxiliary police, to ordinary people and dissidents governed as ‘special households,’” and for the mantra ‘Follow the party and prosper: oppose it and die’ to be encoded into the minds of all Chinese citizens,” he wrote.

“The position of the Chinese government since the massacre has prevented full disclosure about what really happened. The victims are still referred to as thugs and their spirits have yet to be laid to rest.” — Li Jinjin

Li Jinjin, a 1989 Tiananmen Square student protester who had worked as an immigration lawyer after fleeing China at the end of a two-year jail term for joining the pro-democracy protests, was stabbed to death by an angry would-be client on March 14.

Li, 66 at the time of his death, was known as Jim Li during his decades practicing law in New York. Friends described him as a passionate political activist in the overseas pro-democracy movement who relished fierce debates on politics and did pro bono work to help exiled dissidents.

Li served two years’ imprisonment in the wake of the 1989 student-led pro-democracy movement, before going to the U.S. to study law in the 1990s.

Arrested in Li’s office right after the attack, Chinese student Zhang Xiaoning was arraigned on April 13 six counts, including murder in the second degree, weapons charges and harassment, and faces up to 25 years-to-life in prison.

Sources with knowledge of the case said that Zhang raised suspicions she was acting on Beijing’s behalf because she came to the U.S. on a student visa but never enrolled in any classes.

Her attack was believed to have been triggered by Li’s refusal to handle her asylum case.

Zhang told a crowd waiting outside a Queens police station after her arrest that she did not regret her actions.

“Only traitors like you should regret. You’re Chinese yet you oppose the Chinese Communist Party! You have ruined countless students and are about to ruin more,” Zhang yelled, according to local media reports.

Li famously donated his time and money to help clients who couldn’t afford legal representation.

“Li Jinjin’s greatest wish was to end the tyranny of the CCP,” concluded an the obituary penned by dozens of fellow exiled dissidents for Li that praised his belief in the democracy movement, and his personal generosity.

“Russia’s reform is better than China’s.” — Xiong Wei, comment to The Washington Post on May 14, 1989 at Tiananmen protests just before Soviet Union President Mikhail Gorbachev’s arrival in Beijing.

Xiong Wei, who ranked 20th on the list of 21 most wanted student leaders after the Tiananmen crackdown in 1989, died of illness in November at the age of 56.

Less well-known than June 4th Tiananmen student protest leaders such as Wang Dan, Wu’er Kaixi and Zhou Fengsuo, Xiong did not maintain contact with other activists and lived with limited mobility after a stroke several years ago. Reports said he pursued a business career in Beijing.

Xiong was an electronics student at Tsinghua University and the son of a senior Communist Party official. He surrendered to authorities with his mother in northeastern Liaoning province on June 14, 1989, and was not formally charged for his role in the abortive pro-democracy movement.

Zhou said in a tweet on Nov. 20 revealing Xiong’s death that the two were inmates back in Beijing’s Qincheng Prison, but after Xiong’s release from prison, he seldom contacted other people. Zhou and Xiong hadn’t met up until a Tiananmen alumni reunion several years ago.

Few details on his career and death are available.

“[He was] smart, resourceful, empathetic, and with a practical and intuitive understanding of economic policy-making to boot.” — Sean Turnell, the former economic advisor to deposed State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi, about Khin Maung Shwe.

Khin Maung Shwe, a Muslim political prisoner and former parliamentary candidate accused of plotting acts of terrorism, was beaten to death by prison guards in Myanmar last year, but his death was only disclosed to the outside world last month.

The 44-year-old activist, also known as Ya Kut Bai, was beaten and kicked to death after trying to mediate in a fight in Yangon’s notorious Insein Prison, said Sean Turnell, the former economic advisor to deposed State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi.

Turnell, an Australian national who was released from prison by the Myanmar military junta in a general amnesty on Nov. 17 after nearly two years behind bars, wrote in a post to his Facebook account that Khin Maung Shwe was “a hero who I will honor as long as I live.”

Former political prisoner Thiha Win Tin told RFA that Khin Maung Shwe died on Nov. 18, 2021, from internal injuries he suffered in a brutal beating a day earlier.

The beating was ordered by the prison warden after Khin Maung Shwe had intervened in a brawl and carried out by guards including one who had voiced hatred for Myanmar’s Muslims, who make up who make up about 4% of Myanmar’s 55.8 million people and face discrimination in society.

Turnell told RFA via email that Khin Maung Shwe was the most admirable human being he had ever known and the kind of person who could have changed Myanmar for the better.

“[He was] smart, resourceful, empathetic, and with a practical and intuitive understanding of economic policy-making to boot,” Turnell wrote.

Khin Maung Shwe helped him secure food, taught him how to keep his clothes clean and dry, and “provided me with all the implements I needed to stay alive” while incarcerated, Turnell added.

“In numerous acts of incredible generosity he shared whatever he had, and defended me against some of the guards who tried to intimidate this ‘foreigner.’ He had not much himself except his courage, compassion and humanity.”

According to the Assistance Association for Political Prisoners, a Thailand-based Burmese NGO, the junta has arrested more than 16,520 people in the 22 months since the coup, and more than 13,000 are still in detention. More than 2,500 coup opponents have been killed.

Reporting by RFA Mandarin and Burmese. Written by Paul Eckert. Illustrations by Amanda Weisbrod / RFA