INTERVIEW: ‘Our interviewees share sensitive stories that could get them arrested’

Share

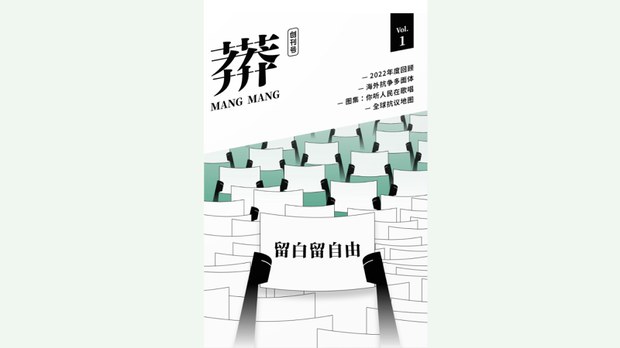

Chinese university students studying overseas have founded the independent magazine Mang Mang with the goal of maintaining the momentum of the “white paper” protest movement.

A group of Chinese students at overseas universities has set up a political magazine to carry forward the momentum of the “white paper” protest movement, a wave of spontaneous demonstrations that swept major cities in late November. Sparked by a fatal lockdown fire in an apartment building in Xinjiang’s regional capital Urumqi, the protests also took aim at the rolling lockdowns, mass surveillance and compulsory testing of the zero-COVID policy. Some protesters held up blank sheets of A4 printer paper and others called on President Xi Jinping to step down and call elections. Magazine co-founder Tong Sheng told RFA Mandarin about the new publication’s mission.

RFA: So how did the project start?

Tong Sheng: After meeting in Berlin, several like-minded friends got together to discuss things, and decided to start a magazine to make our own effort to fight for a little space for expression.

RFA: The first issue of Mang Mang, which could be rendered as “reckless” in English, with connotations of rampantly growing plants, was officially published on New Year’s Eve with the rubric “remembering the little things of our time.”

Tong Sheng: Recording the minutiae of the era we live in is our main task. Firstly, we have noticed that the collective memory of people living in China, whether it’s their memories of protests or other forms [of dissent], is constantly being tampered with through repeated propaganda. The regime now controls so much of the discourse and channels of information, and won’t allow any other [non-state] journalists to speak out or engage in objective reporting.

Meanwhile, censorship is getting stricter and stricter. They used to just censor the news, then they moved to public accounts on WeChat, then to comments on Weibo, with more and more keyword searches being censored all the time.

People are being suffocated; we have no way to speak out. We think that, to counter this trend, there is a need for small platforms that are able to host these memories of the brutal things this regime has done to us, as well as things that have happened to marginalized people around the world or various parts of China, whose voices have been overshadowed by the mainstream.

We can’t just let [debate and information] come and go in waves, as it does at the moment on the internet — we need a record.

RFA: For your first issue, you interviewed people who took part in the white paper movement, Chinese transgender people seeking asylum and a psychologist working in China. What were the biggest obstacles to doing that reporting?

Tong Sheng: The biggest problem of all when talking to people in China is their safety, and how to maintain the information security of both parties during the interview. The second-biggest is one of trust and expectation. Our interviewees share very sensitive stories with us that could get them arrested. How can we meet that trust, and those expectations? We can’t pay anyone; we can barely afford our own printing costs. So we need to ask ourselves if we are conveying what they are saying to our readers correctly.

During the production process, the part that moved me the most was the round-table talks, for which we distributed questionnaires to allow more [white paper movement] participants to have their voices heard. Their comments were the simplest and most direct. For many, this was the first time they had taken to the streets. Some were in China and some overseas, all sharing their anger, and their expectations. Many of them had high expectations of us, too, which both motivated us and put us under pressure.

RFA: Are the other Mang Mang editors all overseas students like you?

Tong Sheng: There are more than 10 people in the Mang Mang team. Some have jobs, but most of them are overseas students. Some are majoring in media … so this is a way to put their ideals into practice.

RFA: What does Mang Mang hope to achieve in 2023?

Tong Sheng: There have been a lot of obstacles and difficulties to overcome just to produce the first issue, and we poured a lot of energy into it, to bring it to print. We need to find a way to have the team work in a sustainable manner and to raise the necessary funds, so everyone can devote all of their energy to the magazine.

We hope Mang Mang can play a part in the new wave of transformation that has swept [China] since the protests … [For example], there are workshops and book clubs being set up in a lot of places. We hope to defend our collective memory.

Translated by Luisetta Mudie. Edited by Malcolm Foster.